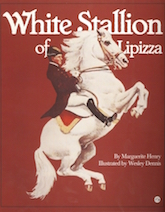

As much as King of the Wind filled my tween heart and soul, this other Marguerite Henry classic came to mean more to me when I grew out of tween and teenhood. I could dream of owning (or being owned by) an Arabian someday, but the white horses of Vienna, the fabled Lipizzans, were not for the mere and mortal likes of me. They were and are state treasures of Austria. I could worship them from afar. I might even be able to ride the movements they made famous, but on other breeds of horses. If I had a dream in that direction, it was to ride a Lipizzaner once, and then, I told myself, I would be content.

The universe always laughs at us. Sometimes even in a good way.

At the time I first read and reread White Stallion of Lipizza, the book was fairly new. It was published in 1964, the year the Spanish Riding School toured the US. My childhood best friend got to see them in Boston, and sit in the royal box next to General Patton’s widow. She came home full of the beauty and magic of the performance and the horses. We used to chant their names like incantations. Siglavy Graina. Maestoso Alea. And our mellifluous favorite, Conversano Montebella.

For us, the story of Hans Haupt, the baker’s son who dreams of riding a white stallion in the Winter Riding Hall of Vienna, was a dream in itself. Hans lives for a glimpse of the white stallions in the streets in the mornings, when he makes deliveries in his father’s cart, pulled by the loyal and kind but undistinguished mare, Rosy. He learns all about the breed with the help of a friendly and supportive librarian; he visits the stud farm at Piber and met the mares and foals the young stallions; finally, triumphantly, he is given a ticket to a performance, to sit in the royal box, no less (just like my friend).

For us, the story of Hans Haupt, the baker’s son who dreams of riding a white stallion in the Winter Riding Hall of Vienna, was a dream in itself. Hans lives for a glimpse of the white stallions in the streets in the mornings, when he makes deliveries in his father’s cart, pulled by the loyal and kind but undistinguished mare, Rosy. He learns all about the breed with the help of a friendly and supportive librarian; he visits the stud farm at Piber and met the mares and foals the young stallions; finally, triumphantly, he is given a ticket to a performance, to sit in the royal box, no less (just like my friend).

But that’s only the beginning of his obsession. Not only does he teach Rosy a very general approximation of the stallions’ slow-motion trot, the passage, but he begs to be admitted to the school as a student. The Director tells him to wait until he’s older, but through a fortunate combination of circumstances, he’s hired to handle one of the stallions, Maestoso Borina, during performances of an opera. Borina forms a bond with Hans, but he’s very much his own person, and he is an Airs horse. He does the courbette, the great leap when the horse rises to his full height and jumps forward—as many as ten jumps, though two or three are more normal.

He becomes so caught up in his part in the opera that on opening day, when he’s supposed to carry the great soprano, Maria Jeritza, onstage for the dramatic final scene, he does so in a full courbette. Jeritza fortunately is a fine rider and stays on, and the scene is a sensation.

Hans is admitted to the School after this, and the story follows him through the long, exacting process of becoming a Riding Master or Bereiter. Borina is his “four-legged professor,” and he dreams incessantly of riding the courbette, but it takes years to reach that point—and on the first try, he literally hits dirt. But in the end, he masters the Air, and performs it in a gala in front of the Prince of Wales; and then he finally understands what it’s really about. It’s not about his glory or his accomplishments. It’s about the horse. In the epilogue we learn that Borina, who was nearly thirty at that point, continued to be a star for a few more years, until, at thirty-three, he lay down for the last time.

As a kid I loved this book, of course, but as I grew older and started learning the art of dressage, all the details of riding and training became real to me. Then I saw the Spanish Riding School in performance myself, from a ringside seat in Madison Square Garden. I watched them as they danced past me, and looked into their eyes, and saw the deep, quiet focus, with all their souls turned inward. And that was what it was really about. I understood what Hans understood, at the end of Henry’s book.

And then, not quite a decade later, as I was moving from Connecticut to Arizona and searching for a horse of my own after years of leasing and borrowing, my instructor said to me, “You should look for a Lipizzan.”

But, I said, ordinary mortals can’t own them. They’re state treasures of Austria.

“Of course you can,” he answered. “And here are two young mares for sale, right there in Arizona. Call and ask for a video.”

So I did. And in the fullness of time, when I was in Arizona and he was still in Connecticut, he sent word: “Go up there. Buy the older sister.”

I went up to the high country near Flagstaff, among the pines, and saw pastures full of short, sturdy white horses. But one young mare came out from the rest and looked at me, and I never even asked to ride the other sister. By afternoon when we took her to be vetted (a prepurchase vet exam is a good thing when buying a horse), she pulled away from her trainer and pressed against me. I was ever so relieved when she passed her exam. If she hadn’t, I didn’t know what I would have done.

Later I learned that she was descended from our favorite horse from the 1964 tour: Conversano Montebella. It felt in many ways as if the world had come full circle.

That was twenty-six years ago. Last week, two and a half weeks after her thirtieth birthday, I said goodbye to her. She’s buried outside the riding arena where we spent so many hours together, in sight of the other Lipizzans who came to join us over the years—most of them born here, and one of them her son.

I had a very hard time opening this book and rereading it, knowing I’d probably bawl my way through it. Over the years I’ve learned that the story is based on several collections of true stories. The Spanish Riding School, of course, and its dancing white stallions (and some of the riders now are women). Maestoso Borina was a real horse. Maria Jeritza was a real opera singer, and she was so captivated by the breed that she ended up importing three Lipizzans to the US in 1937, the first of their kind in this country. Colonel Podhajsky, the Director, was very much a real person, featured prominently in a Disney movie, “The Miracle of the White Stallions,” with many books under his own name, and many more about him and his exploits. Hans’ story is also based on a true one, though it’s said that the animals the Viennese boy trained to dance were a pair of goats. (One case in which truth is indeed stranger than fiction.)

This is one of those books that’s even more true than the historical truth that’s in it. It gets its subject absolutely right. The riding. The training. The horses. All the way to the end, where it says,

Filled with the wisdoms of life, Borina died in the springtime of his thirty-third year. Meanwhile, far off in the Alpine meadows of Piber, pitch-black foals, full of the exuberant joy of life, were dancing and prancing. With no audience but their mothers, and no music except wind whispers, they were leaping into the air for the sheer fun of it.

And so the circle is complete.

Next time in our summer reading adventure, I’ll turn to another lifelong favorite, Mary Stewart’s Airs Above the Ground. More dancing white horses—this time with grownup protagonists, but still All The Feels.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. She’s even written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. Her most recent short novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.